The resistant starch foods list pdf provides a comprehensive guide to a fascinating dietary component that’s transforming how we approach gut health and overall well-being. Resistant starch, unlike other starches, bypasses digestion in the small intestine and instead, acts as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial bacteria in your colon. This seemingly simple concept unlocks a cascade of benefits, from improved blood sugar control to enhanced weight management.

This guide will dissect the science, the sources, and the practical application of resistant starch in your daily life.

This comprehensive resource will explore the science behind resistant starch, differentiating it from other starch types and highlighting its impact on the gut microbiome. We’ll delve into the benefits of consuming resistant starch, including its effects on blood sugar control, weight management, and satiety. You will also discover the best sources of resistant starch, both natural and processed, along with practical tips for incorporating these foods into your diet.

We’ll also address potential side effects, recommended dosages, and considerations for individuals with specific health conditions.

Introduction to Resistant Starch Foods

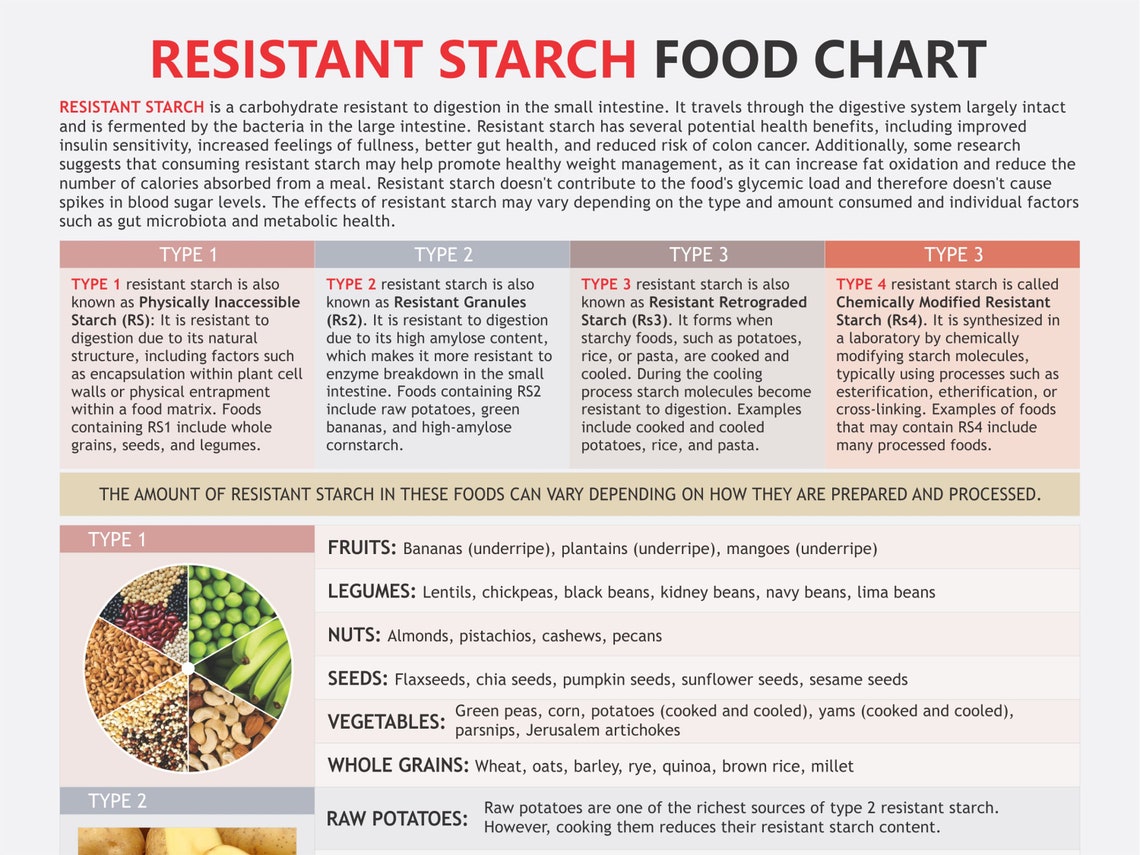

Resistant starch is a type of starch that resists digestion in the small intestine, behaving more like fiber. This unique characteristic offers a range of health benefits, particularly for gut health and overall metabolic function. Unlike readily digestible starches, resistant starch passes through the small intestine undigested and is fermented by bacteria in the large intestine. This fermentation process produces beneficial byproducts that contribute to a healthy gut environment.

Resistant Starch and Its Distinction from Other Starches

Resistant starch differs significantly from other starches, primarily due to its structure and how the body processes it. Most starches, like those found in white bread or potatoes, are rapidly digested and broken down into glucose in the small intestine, leading to a quick rise in blood sugar levels. In contrast, resistant starch is not broken down in the small intestine.

Instead, it travels to the large intestine, where it is fermented by gut bacteria. This slow digestion process offers several advantages.

Benefits of Consuming Resistant Starch

Incorporating resistant starch into your diet can provide a variety of health advantages. These benefits stem from its unique properties, including its impact on blood sugar regulation, gut health, and satiety.

- Improved Blood Sugar Control: Resistant starch has a low glycemic index, meaning it doesn’t cause a rapid spike in blood sugar levels. This is because it is not digested in the small intestine and doesn’t release glucose quickly. This can be particularly beneficial for individuals with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes. A study published in the

-Journal of Nutrition* found that consuming resistant starch improved insulin sensitivity in participants. - Enhanced Gut Health: As a prebiotic, resistant starch feeds the beneficial bacteria in the gut. This fermentation process promotes the growth of a diverse and healthy microbiome.

- Increased Satiety: Resistant starch can increase feelings of fullness and satiety, potentially aiding in weight management. This is because it takes longer to digest and may influence the release of hormones that regulate appetite. A meta-analysis of studies published in the

-American Journal of Clinical Nutrition* found that resistant starch consumption was associated with increased satiety and reduced food intake. - Improved Digestive Health: The fermentation of resistant starch in the colon produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, which can improve colon health. Butyrate is a primary energy source for the cells lining the colon and has anti-inflammatory properties.

Role of Resistant Starch in Gut Health and the Microbiome

Resistant starch plays a crucial role in maintaining a healthy gut microbiome, influencing overall health. It acts as a prebiotic, meaning it serves as food for the beneficial bacteria in the large intestine. This fermentation process not only increases the population of these beneficial bacteria but also produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

The fermentation of resistant starch in the colon produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate.

- Promotion of Beneficial Bacteria: Resistant starch encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria like

-Bifidobacteria* and

-Lactobacilli*. These bacteria help crowd out harmful bacteria, contribute to immune function, and aid in the digestion of other foods. - Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): SCFAs, particularly butyrate, are a major byproduct of resistant starch fermentation. Butyrate is a primary energy source for colon cells, promoting their health and function. It also has anti-inflammatory properties and may help protect against colon cancer.

- Improved Gut Barrier Function: The SCFAs produced from resistant starch fermentation can strengthen the gut barrier, preventing the leakage of harmful substances into the bloodstream (leaky gut). This improved barrier function reduces inflammation and supports overall health.

- Reduced Inflammation: Resistant starch can reduce inflammation in the gut. The SCFAs, particularly butyrate, have anti-inflammatory effects that help to maintain a balanced gut environment. Chronic inflammation in the gut is linked to various health problems, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Benefits of Resistant Starch

Resistant starch offers a wealth of health advantages, stemming primarily from its unique ability to resist digestion in the small intestine and ferment in the large intestine. This fermentation process fuels the production of beneficial compounds and promotes various physiological benefits, influencing metabolic health, weight management, and overall well-being. Understanding these benefits can empower individuals to make informed dietary choices and harness the power of resistant starch.

Blood Sugar Control and Insulin Sensitivity

Resistant starch plays a significant role in regulating blood sugar levels and improving insulin sensitivity. Unlike rapidly digested carbohydrates, resistant starch doesn’t cause a sharp spike in blood glucose. This is because it bypasses digestion in the small intestine, leading to a slower and more gradual release of glucose into the bloodstream. This gentle rise in blood sugar helps prevent insulin resistance and reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.The impact on insulin sensitivity is also noteworthy.

Studies have shown that consuming resistant starch can enhance the body’s response to insulin, allowing cells to utilize glucose more effectively. This improved insulin sensitivity can lead to better glucose control and reduced risk of metabolic disorders.Here’s a breakdown of how resistant starch achieves this:

- Slowed Glucose Release: Resistant starch is not broken down into glucose in the small intestine, which prevents the rapid absorption of sugar into the bloodstream.

- Improved Insulin Sensitivity: Resistant starch may enhance insulin’s ability to work, allowing glucose to be used more efficiently by cells.

- Reduced Postprandial Glucose Response: Eating resistant starch results in a lower blood sugar response after meals, contributing to better overall glucose control.

Consider this real-world example: A study published in theAmerican Journal of Clinical Nutrition* found that replacing some refined carbohydrates with resistant starch significantly improved postprandial glucose and insulin responses in individuals with type 2 diabetes. This highlights the potential of resistant starch as a dietary tool for managing blood sugar levels.

Comparison of Resistant Starch with Soluble and Insoluble Fiber

Resistant starch, soluble fiber, and insoluble fiber are all types of dietary fiber, but they differ in their chemical structure, how they’re digested, and their impact on the body. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for optimizing dietary choices and maximizing health benefits.Here’s a table comparing the key characteristics and effects of each type of fiber:

| Fiber Type | Digestibility | Mechanism of Action | Primary Benefits | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant Starch | Resists digestion in the small intestine; fermented in the large intestine | Feeds beneficial gut bacteria; produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) | Improved blood sugar control, enhanced insulin sensitivity, improved gut health, weight management | Green bananas, cooked and cooled potatoes, beans, lentils, certain grains |

| Soluble Fiber | Dissolves in water | Forms a gel-like substance in the digestive tract; slows digestion | Lowers cholesterol, regulates blood sugar, promotes satiety | Oats, barley, beans, lentils, fruits (apples, citrus), psyllium |

| Insoluble Fiber | Does not dissolve in water | Adds bulk to the stool; promotes regularity | Promotes bowel regularity, prevents constipation, supports gut health | Whole grains, vegetables (leafy greens, broccoli), nuts, seeds |

While all three types of fiber contribute to overall health, resistant starch uniquely offers a combination of benefits related to blood sugar control, gut health, and weight management. Soluble fiber excels at lowering cholesterol and regulating blood sugar, whereas insoluble fiber is primarily known for its role in promoting digestive regularity.

Weight Management and Satiety, Resistant starch foods list pdf

Resistant starch can be a valuable tool for weight management due to its impact on satiety and energy balance. By promoting feelings of fullness and reducing overall calorie intake, resistant starch can support weight loss and prevent weight gain.Here’s how resistant starch contributes to weight management:

- Increased Satiety: Resistant starch can promote satiety by several mechanisms, including slowing gastric emptying, increasing the production of satiety hormones (such as GLP-1), and influencing the gut microbiota. This can lead to reduced food intake and fewer calories consumed throughout the day.

- Reduced Calorie Absorption: Because resistant starch is not fully digested, some of the calories from the food containing it are not absorbed. This can contribute to a slight reduction in overall calorie intake.

- Improved Gut Health: Resistant starch feeds beneficial gut bacteria, leading to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs, such as butyrate, have been linked to improved metabolic health and can influence appetite regulation.

Consider a person incorporating resistant starch into their diet. This person might eat a serving of cooked and cooled potatoes with their meal. Because of the resistant starch content, this person might feel fuller for a longer time, leading them to eat less during the meal and potentially reduce snacking later in the day. Over time, this consistent reduction in calorie intake can contribute to weight loss.

The impact of resistant starch on satiety can be quantified. Research has shown that resistant starch can lead to a significant reduction in energy intake at subsequent meals, highlighting its potential as a tool for weight management.

Sources of Resistant Starch: Resistant Starch Foods List Pdf

Resistant starch is a beneficial type of starch that acts like fiber in the body, promoting gut health and providing other health advantages. Understanding where to find resistant starch in your diet is key to incorporating it effectively. This section will explore the natural sources of resistant starch and how different preparation methods can influence its content.

Naturally Occurring Sources of Resistant Starch

Certain foods naturally contain higher amounts of resistant starch than others. These foods are a great starting point for increasing your intake.

- Green Bananas: Unripe bananas are a rich source of resistant starch, which converts to regular starch as the banana ripens.

- Plantains: Similar to green bananas, plantains offer a significant amount of resistant starch.

- Potatoes (cooked and cooled): Cooling cooked potatoes, such as those used in potato salad, increases their resistant starch content.

- Beans and Legumes: Legumes, including lentils, chickpeas, and kidney beans, are excellent sources of resistant starch.

- Oats: Whole oats, particularly those that are less processed, can contain a good amount of resistant starch.

- Corn: Certain types of corn, like high-amylose corn, are specifically cultivated for their high resistant starch content.

- Rice (cooked and cooled): Similar to potatoes, cooling cooked rice increases the resistant starch content.

Preparation Methods That Enhance Resistant Starch Content

The way you prepare certain foods can significantly impact their resistant starch levels. These methods often involve changes to the starch’s structure.

One of the most effective methods involves cooling cooked starchy foods. This process, known as retrogradation, causes the starch molecules to reorganize, forming more resistant starch. The longer the food is cooled, the more resistant starch is typically formed. For example, cooked potatoes, rice, or pasta that are allowed to cool completely in the refrigerator before being consumed will have a higher resistant starch content than when eaten immediately after cooking.

Another key aspect is the type of cooking method. Boiling, steaming, or baking, which involves less fat and oil, tends to be more conducive to preserving or increasing resistant starch content. Frying, particularly deep-frying, may reduce the resistant starch content due to the introduction of oils and higher temperatures that alter the starch structure.

Differences in Resistant Starch Content Among Various Types of Legumes

Different types of legumes exhibit varying amounts of resistant starch. Understanding these differences can help you optimize your dietary choices for maximum benefit.

Legumes vary in their resistant starch content, but all are good sources. The exact amounts can fluctuate based on factors like variety, growing conditions, and processing methods. It is useful to compare some examples. This is a table that presents estimated resistant starch values for different legumes.

| Legume | Resistant Starch Content (Approximate % of Dry Weight) |

|---|---|

| Navy Beans | 4-6% |

| Kidney Beans | 4-6% |

| Lentils | 3-5% |

| Chickpeas | 3-5% |

| Black Beans | 4-6% |

As you can see, while there are differences, the range of resistant starch content is generally consistent across different types of beans and lentils. Choosing a variety of legumes in your diet ensures a good intake of resistant starch and other essential nutrients.

Sources of Resistant Starch: Resistant Starch Foods List Pdf

While we’ve explored natural sources of resistant starch, it’s also present in processed foods and available as supplements. Understanding these options is crucial for effectively incorporating resistant starch into your diet, as they offer varying levels of convenience and impact on your overall health. However, always prioritize whole, unprocessed foods when possible for a more comprehensive nutritional profile.

Let’s delve into the specifics of these sources, examining both their benefits and potential drawbacks.

Processed Foods with Added Resistant Starch

Certain processed foods are now formulated with added resistant starch to enhance their nutritional profile, often focusing on fiber content. This can be a convenient way to boost your intake, but it’s essential to be mindful of the overall ingredients and processing methods.

Here’s a table highlighting some examples:

| Food Item | Type of Resistant Starch | Approximate Amount of Resistant Starch per Serving | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant Starch Enriched Bread | RS2 (High Amylose Corn Starch) | Varies, check label (e.g., 5-10g per slice) | Often marketed as “high fiber” or “gut-friendly.” Check for added sugars and refined grains. |

| Resistant Starch Enriched Pasta | RS2 (High Amylose Corn Starch) | Varies, check label (e.g., 5-10g per serving) | Similar considerations as bread. Opt for whole-grain versions when possible. |

| Breakfast Cereals | RS2 (High Amylose Corn Starch) | Varies, check label (e.g., 2-8g per serving) | Look for cereals with minimal added sugars and artificial ingredients. |

| Protein Bars/Snack Bars | RS2 (High Amylose Corn Starch) | Varies, check label (e.g., 3-7g per bar) | Often contain other ingredients, including sweeteners and processed fats. Read labels carefully. |

Resistant Starch Supplements

Resistant starch supplements provide a concentrated dose, offering a more controlled way to increase intake. Different types of supplements are available, each with varying properties and effects.

Here’s an overview of the common types of resistant starch supplements:

- RS2 (High-Amylose Corn Starch): This is the most widely available type, derived from corn. It’s relatively inexpensive and has a neutral taste, making it easy to add to foods and beverages. Examples include Hi-Maize and Resistant Starch 2.

- RS3 (Retrograded Starch): Formed when cooked and cooled starches, like potatoes or rice, are allowed to retrograde. Supplements might use retrograded cornstarch or other sources. The exact amount of RS3 can vary depending on the processing.

- RS4 (Chemically Modified Starch): This type involves chemical modifications to the starch to make it resistant to digestion. While it increases resistant starch content, the long-term health effects of some RS4 are not fully understood.

- RS5 (Complexed Starch): These are created by forming complexes with lipids, which makes them more resistant to digestion.

Supplementation dosages typically range from 15 to 30 grams per day, but it’s advisable to start with a smaller amount and gradually increase it to avoid digestive discomfort. Always consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen, especially if you have underlying health conditions.

Pros and Cons: Resistant Starch from Processed Foods vs. Natural Sources

Choosing between processed foods and natural sources involves considering convenience, nutritional value, and potential drawbacks. Here’s a comparison:

| Feature | Resistant Starch from Processed Foods | Resistant Starch from Natural Sources | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience | High. Easy to incorporate into existing diets. | Can require more preparation (e.g., cooking and cooling). | Buying RS-enriched bread vs. cooking and cooling potatoes. |

| Nutritional Profile | Often contains added sugars, unhealthy fats, and additives. May lack other essential nutrients. | Typically provides a wider range of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Often lower in added sugars and unhealthy fats. | A processed cereal versus a serving of cooked and cooled sweet potatoes. |

| Fiber Content | May offer a decent amount of resistant starch but often not a complete fiber profile. | Provides both resistant starch and other types of fiber, contributing to overall gut health. | RS-enriched pasta compared to a serving of cooked lentils. |

| Cost | Can be comparable or more expensive than natural sources, depending on the product. | Generally more cost-effective, especially when buying whole foods in bulk. | Price comparison of RS-enriched bread vs. potatoes or beans. |

| Potential Drawbacks | Risk of consuming added sugars, unhealthy fats, and artificial ingredients. May not be suitable for individuals with sensitivities to certain ingredients. | May require more time for preparation. Could cause digestive discomfort if introduced too quickly. | Digestive issues arising from excess intake of processed foods vs. digestive adaptation to natural sources. |

Preparing and Cooking Resistant Starch Foods

Optimizing your food preparation and cooking methods is crucial to unlocking the full potential of resistant starch. Proper techniques can significantly boost the amount of resistant starch in your meals, maximizing their health benefits. This section provides practical guidance on preparing, cooking, and incorporating resistant starch-rich foods into your diet, ensuring you get the most out of every bite.

Maximizing Resistant Starch in Preparation

Many foods naturally contain some resistant starch, but how you prepare them can significantly impact the final amount. Understanding these preparation techniques allows you to manipulate the starch composition of your food, boosting its resistant starch content.

- Cooling Cooked Starches: The process of cooking and then cooling starchy foods like rice, pasta, and potatoes increases the formation of resistant starch through a process called retrogradation. This is one of the most effective ways to boost resistant starch levels.

- Choosing the Right Foods: Some foods naturally contain more resistant starch than others. Focus on incorporating foods like green bananas, unripe plantains, and certain legumes, as these are naturally higher in resistant starch.

- Proper Storage: Store cooked and cooled starchy foods in the refrigerator for optimal retrogradation. The longer the cooling period, the more resistant starch is formed, though the effect plateaus over time.

Cooking and Cooling Rice for Increased Resistant Starch

Cooking and cooling rice is a simple yet effective method for increasing its resistant starch content. The specific cooking method and subsequent cooling process play critical roles in maximizing this effect.

Follow these steps for cooking and cooling rice to increase its resistant starch:

- Select the Right Rice: White rice, especially long-grain varieties like basmati, can be cooked and cooled to increase its resistant starch content. Brown rice also works well, but the presence of the bran may slightly affect the final amount.

- Cooking Method: Cook the rice using the absorption method. Add the rice to boiling water (or broth) in a pot, reduce the heat to low, cover, and simmer until all the water is absorbed and the rice is tender. This ensures even cooking.

- Cooling the Rice: Once cooked, immediately transfer the rice to a clean container and spread it out in a thin layer. Allow the rice to cool completely at room temperature (approximately 20-30 minutes).

- Refrigeration: After cooling at room temperature, place the rice in the refrigerator for at least 12 hours, or ideally overnight. This extended cooling period allows for maximum retrogradation and the formation of resistant starch.

- Reheating (Optional): You can reheat the rice before consumption. However, reheating may slightly decrease the resistant starch content. Try to reheat it only once and do so gently. Consider eating it cold to retain the maximum amount of resistant starch.

The process of cooling cooked rice for at least 12 hours in the refrigerator can increase its resistant starch content by a significant amount, potentially up to tenfold, compared to freshly cooked rice.

Resistant Starch Recipes

Incorporating resistant starch-rich foods into your diet doesn’t have to be complicated. Here are some recipe ideas that highlight resistant starch sources, ensuring a delicious and beneficial culinary experience.

These recipes incorporate resistant starch-rich ingredients:

- Green Banana Smoothie: This smoothie uses green bananas as a base. Combine one peeled green banana (pre-cut and frozen for better texture), a cup of unsweetened almond milk, a handful of spinach, and a scoop of protein powder. Blend until smooth. The green banana provides a significant dose of resistant starch.

- Overnight Oats with Chia Seeds and Cooked and Cooled Rice: Prepare overnight oats using rolled oats, chia seeds, and cooked and cooled rice (from the cooking and cooling guide above). Combine the ingredients with almond milk, a sweetener of your choice (like stevia or a small amount of maple syrup), and a dash of cinnamon. Let it sit in the refrigerator overnight. The chia seeds add fiber, while the cooled rice and oats contribute resistant starch.

- Black Bean Salad with Unripe Plantains: Combine cooked black beans, chopped red onion, bell peppers, and cilantro. Dice an unripe plantain and lightly sauté or roast it until tender but still firm. Add the plantain to the salad and dress with a lime vinaigrette. The unripe plantain and black beans are rich sources of resistant starch.

- Cold Potato Salad: Use cooked and cooled potatoes as the base. Boil the potatoes until tender. Allow them to cool completely in the refrigerator before dicing. Mix the cooled potatoes with a dressing of mayonnaise (or a healthier alternative like Greek yogurt), mustard, celery, and onion.

Dosage and Consumption of Resistant Starch

Understanding the right amount of resistant starch to consume and how your body reacts to it is crucial for maximizing its benefits and minimizing any potential discomfort. This section will delve into the recommended daily intake, potential side effects, and factors influencing individual tolerance, providing you with the knowledge to incorporate resistant starch into your diet safely and effectively.

Recommended Daily Intake of Resistant Starch

Determining the optimal daily intake of resistant starch is not an exact science, as individual needs vary. However, general guidelines can help you establish a starting point.The recommended daily intake of resistant starch generally ranges from 15-20 grams per day. This amount is often associated with noticeable improvements in gut health, blood sugar control, and satiety. However, it’s essential to start slowly and gradually increase your intake to allow your digestive system to adapt.Consider this example: a medium-sized cooked potato, cooled and reheated, might contain around 4-5 grams of resistant starch.

Therefore, to reach the lower end of the recommended range, you might aim to consume several servings of resistant starch-rich foods throughout the day.

Potential Side Effects of Excessive Resistant Starch Consumption

While resistant starch offers numerous benefits, consuming too much, especially when you’re not accustomed to it, can lead to some unpleasant side effects. These side effects are generally related to the fermentation process that occurs in the gut.

- Gas and Bloating: Increased fermentation produces gases like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide, which can cause bloating and discomfort.

- Flatulence: The same gases that cause bloating can also lead to increased flatulence.

- Diarrhea or Constipation: The altered gut environment and changes in stool consistency can result in either diarrhea or constipation, depending on the individual and the amount of resistant starch consumed.

- Abdominal Cramps: Some individuals may experience abdominal cramps or discomfort as their digestive system adjusts.

It’s crucial to listen to your body and adjust your intake accordingly. If you experience any of these side effects, reduce your resistant starch consumption and gradually increase it again as your body adapts. Remember, patience is key.

Factors Influencing Individual Tolerance to Resistant Starch

Several factors can influence how well your body tolerates resistant starch. Understanding these factors can help you personalize your approach to incorporating resistant starch into your diet.

- Individual Gut Microbiome Composition: The composition of your gut bacteria plays a significant role. Individuals with a more diverse and healthy gut microbiome may tolerate resistant starch better. This is because they have a wider range of bacteria capable of fermenting resistant starch without producing excessive gas.

- Existing Digestive Health Conditions: Individuals with pre-existing digestive issues, such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) or Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), may be more sensitive to resistant starch. It’s crucial to consult with a healthcare professional if you have any of these conditions before significantly increasing your resistant starch intake.

- Dietary Habits: Your overall diet influences tolerance. If your diet is already high in fiber, your body may be better equipped to handle the additional fermentation. However, a sudden increase in fiber intake, including resistant starch, can overwhelm the system.

- Gradual Introduction: The rate at which you introduce resistant starch is critical. Starting with small amounts and gradually increasing your intake allows your gut bacteria to adapt, minimizing side effects. For example, begin with a small serving of cooked and cooled rice or potatoes and slowly increase the portion size over several weeks.

- Food Preparation Methods: How you prepare resistant starch-rich foods can affect tolerance. Cooling and reheating starchy foods, such as potatoes and rice, increases their resistant starch content. However, different preparation methods may also influence how easily the starch is fermented.

The key takeaway is that there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Paying attention to your body’s signals and making adjustments as needed is the best way to determine your optimal resistant starch intake.

Research and Studies on Resistant Starch

Resistant starch has garnered significant attention from the scientific community due to its potential health benefits. Numerous studies have investigated its impact on various aspects of human health, from gut microbiota modulation to metabolic improvements. This section delves into recent research findings, methodologies employed, and the limitations inherent in the current body of work on resistant starch.

Recent Scientific Studies on the Effects of Resistant Starch on Various Health Conditions

The impact of resistant starch has been explored across a spectrum of health conditions, with studies continually emerging. Here’s a look at some of the most significant areas of investigation:

- Gut Health and Microbiota: Several studies have focused on the prebiotic effects of resistant starch. Research indicates that resistant starch acts as a fermentable substrate in the colon, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. For example, a study published in the

-American Journal of Clinical Nutrition* demonstrated that consumption of high-amylose maize starch (a type of resistant starch) significantly increased the abundance of these beneficial bacteria in the gut, leading to improvements in gut barrier function and reduced inflammation. - Metabolic Health: The role of resistant starch in improving metabolic parameters, such as insulin sensitivity and glucose control, is another area of intense research. Studies have shown that resistant starch can improve postprandial glucose and insulin responses. A meta-analysis of several randomized controlled trials, published in

-Diabetes Care*, revealed that resistant starch supplementation was associated with a significant reduction in fasting insulin levels and improved insulin sensitivity in individuals with insulin resistance. - Weight Management: Research suggests that resistant starch may aid in weight management by increasing satiety and reducing calorie intake. The slow digestion of resistant starch can lead to a prolonged feeling of fullness, which can contribute to reduced food consumption. A study in the

-International Journal of Obesity* found that adding resistant starch to meals led to reduced subsequent food intake and increased fat oxidation in overweight individuals. - Colorectal Cancer Prevention: Some studies have explored the potential of resistant starch in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer. The fermentation of resistant starch in the colon produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, which have been shown to have anti-cancer properties. While more research is needed, preliminary findings suggest that resistant starch may protect against colorectal cancer development.

Methodologies Used in Research to Measure the Impact of Resistant Starch

Researchers employ a variety of methodologies to assess the effects of resistant starch. These methods are crucial for obtaining accurate and reliable data.

Notice food moth traps for recommendations and other broad suggestions.

- Dietary Interventions: This is a common approach where participants are given specific amounts of resistant starch in their diet, either through food or supplements. Researchers carefully control the participants’ diets and monitor their health parameters over a defined period.

- Fecal Analysis: Analyzing fecal samples is crucial for assessing the impact of resistant starch on the gut microbiota. This involves measuring the composition of bacteria, levels of SCFAs, and other biomarkers related to gut health. For example, techniques like 16S rRNA gene sequencing are used to identify and quantify different bacterial species.

- Blood Tests: Blood samples are used to measure metabolic parameters, such as glucose, insulin, cholesterol, and inflammatory markers. These tests help researchers evaluate the effects of resistant starch on insulin sensitivity, lipid profiles, and overall metabolic health.

- Glucose Tolerance Tests: These tests are used to assess how the body processes glucose. Participants are given a glucose load, and their blood glucose and insulin levels are measured over time. Resistant starch’s impact on glucose metabolism can then be evaluated.

- Imaging Techniques: In some studies, imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are used to assess changes in body composition, such as fat distribution. This can help to determine the effects of resistant starch on weight management and metabolic health.

Limitations of Current Research on Resistant Starch

Despite the progress made, several limitations exist in the current research on resistant starch. Addressing these limitations is crucial for advancing our understanding of its health benefits.

- Variability in Resistant Starch Types: Different types of resistant starch have varying properties and effects. Research often fails to distinguish between these types, making it difficult to compare results and draw definitive conclusions. For instance, resistant starch type 2 (found in green bananas) may have different effects than resistant starch type 3 (retrograded starch).

- Dosage and Duration of Studies: The optimal dosage and duration of resistant starch supplementation are still being investigated. Studies often use different dosages and intervention periods, making it difficult to establish consistent recommendations. A long-term study evaluating the effects of varying doses over several years is lacking.

- Heterogeneity of Study Populations: Participants in studies often vary in age, health status, and dietary habits. This variability can affect the results and make it challenging to generalize findings to the wider population. For example, a study on individuals with type 2 diabetes might yield different results than a study on healthy individuals.

- Lack of Standardized Measurement Methods: There is a need for standardized methods to measure resistant starch content in foods and supplements. Different analytical techniques can yield varying results, which can complicate comparisons across studies.

- Mechanistic Understanding: While studies have shown the benefits of resistant starch, the precise mechanisms by which it exerts its effects are not fully understood. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific pathways involved.

Integrating Resistant Starch into Your Diet

Incorporating resistant starch into your daily routine can be a straightforward process with a little planning. This section provides practical strategies to seamlessly integrate resistant starch foods into your diet, offering a sample meal plan, dietary adaptation tips, and complementary food pairings to maximize the benefits. This will ensure you’re not only consuming resistant starch but also doing so in a way that aligns with your individual needs and preferences.

Sample Meal Plan Incorporating Resistant Starch Foods for a Week

A well-structured meal plan can help you consistently consume resistant starch throughout the week. This sample plan provides a starting point, but it can be adjusted to suit your individual preferences and caloric needs. Remember to consult with a healthcare professional or registered dietitian for personalized dietary advice.

Here’s a sample week-long meal plan incorporating resistant starch:

| Day | Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Snacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Overnight oats (prepared with rolled oats, chia seeds, and almond milk) with berries | Cold potato salad (potatoes cooked, cooled, and mixed with olive oil, vinegar, and herbs) with grilled chicken salad | Lentil soup with a side of whole-grain bread (optional) | Unripe banana, a handful of almonds |

| Tuesday | Cold cooked rice (refrigerated overnight) with a fried egg and vegetables | Quinoa salad with black beans, corn, and bell peppers (cooled and served cold) | Bean and vegetable chili with a side of plain yogurt (optional) | Green banana chips |

| Wednesday | Overnight oats (prepared with rolled oats, chia seeds, and almond milk) with apple slices | Leftover bean and vegetable chili | Pasta (cooled and served cold) with a tomato-based sauce and grilled vegetables | A small portion of chilled potatoes |

| Thursday | Cold cooked rice (refrigerated overnight) with avocado and a sprinkle of everything bagel seasoning | Lentil salad with mixed greens and a light vinaigrette | Chicken and vegetable stir-fry with a side of cold rice | Unripe banana |

| Friday | Overnight oats (prepared with rolled oats, chia seeds, and almond milk) with peaches | Cold potato salad with tuna | Bean burritos with whole-wheat tortillas (optional), lettuce, and salsa | A handful of nuts |

| Saturday | Cold cooked rice (refrigerated overnight) with a smoothie (banana, berries, spinach, and almond milk) | Leftover bean burritos | Pizza (cooled and served cold) with whole-wheat crust (optional) | Green banana |

| Sunday | Overnight oats (prepared with rolled oats, chia seeds, and almond milk) with blueberries | Quinoa salad with chickpeas, cucumber, and feta cheese (optional) | Vegetable curry with a side of cold rice | Plantain chips |

This meal plan emphasizes the importance of cooling and reheating starchy foods to maximize their resistant starch content. This meal plan provides a diverse range of foods, ensuring a balanced intake of nutrients while also incorporating resistant starch. This is just a sample plan, and you can adjust the meals and portions based on your dietary preferences and individual needs.

Tips for Incorporating Resistant Starch into Your Diet for Individuals with Dietary Restrictions

Individuals with dietary restrictions can still enjoy the benefits of resistant starch. Adaptations are necessary for gluten-free and vegan diets to ensure that they align with these restrictions. Here are some strategies for incorporating resistant starch while adhering to specific dietary needs.

* Gluten-Free Diet:

- Choose gluten-free sources of resistant starch such as green bananas, cooked and cooled white rice, and potatoes.

- Opt for gluten-free oats, ensuring they are certified gluten-free to avoid cross-contamination.

- Carefully check food labels for hidden gluten in processed foods.

- Experiment with quinoa, a gluten-free grain, prepared and cooled for resistant starch benefits.

* Vegan Diet:

- Focus on plant-based sources of resistant starch like green bananas, cooked and cooled rice and potatoes, lentils, beans, and oats.

- Include legumes like lentils and beans in various dishes such as soups, stews, and salads.

- Utilize plant-based milk (e.g., almond, soy, or oat milk) for overnight oats or smoothies.

- Incorporate nuts and seeds for added nutrients and healthy fats.

By understanding these adaptations, individuals with dietary restrictions can still effectively include resistant starch in their diet, ensuring they can experience its health benefits without compromising their dietary needs.

List of Food Pairings that Complement Resistant Starch’s Benefits

Combining resistant starch with specific foods can enhance its effects. Certain food pairings can provide synergistic benefits, improving digestion, and increasing satiety. The following are examples of food pairings that can complement resistant starch.

* Resistant Starch and Probiotics: Pairing resistant starch with probiotic-rich foods can create a beneficial environment for gut health.

- Examples: Overnight oats (resistant starch) with yogurt (probiotics), or a salad with a lentil base (resistant starch) and a side of fermented vegetables like sauerkraut (probiotics).

- Benefits: Probiotics feed on resistant starch, which can help increase the population of beneficial bacteria in the gut.

* Resistant Starch and Fiber: Combining resistant starch with other sources of fiber can further enhance digestive health and promote satiety.

- Examples: A serving of cooled potatoes (resistant starch) with a side of broccoli (fiber), or a bean salad (resistant starch and fiber) with mixed vegetables.

- Benefits: Fiber supports regular bowel movements and helps to regulate blood sugar levels.

* Resistant Starch and Healthy Fats: Adding healthy fats to meals containing resistant starch can improve nutrient absorption and enhance satiety.

- Examples: Cold rice (resistant starch) with avocado (healthy fats), or overnight oats (resistant starch) with a handful of nuts or seeds (healthy fats).

- Benefits: Healthy fats can help slow down digestion, promoting a feeling of fullness, and can also help the body absorb fat-soluble vitamins.

* Resistant Starch and Protein: Pairing resistant starch with protein can further increase satiety and support muscle health.

- Examples: Lentil soup (resistant starch and protein) with a side of grilled chicken or fish (protein), or a salad with quinoa (resistant starch and protein) and chickpeas (protein).

- Benefits: Protein helps with muscle repair and growth, and also contributes to a feeling of fullness.

By incorporating these food pairings, individuals can optimize the benefits of resistant starch and support overall health.

Considerations and Cautions

While resistant starch offers numerous health benefits, it’s crucial to approach its integration into your diet with careful consideration. This section highlights potential risks and provides guidance to ensure a safe and effective experience. It’s important to understand how resistant starch might interact with pre-existing health conditions, the importance of consulting healthcare professionals, and the factors that influence the quality of resistant starch supplements.

Impact on Specific Medical Conditions

Resistant starch can affect individuals differently depending on their underlying health conditions. It’s essential to be aware of these potential interactions.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Some individuals with IBS may experience increased gas, bloating, and abdominal discomfort when consuming resistant starch, particularly in higher doses. The fermentation process in the gut can exacerbate these symptoms. It’s advisable to start with small amounts and gradually increase intake while monitoring for adverse reactions. For example, someone with IBS might initially consume only a teaspoon of green banana flour and gradually increase the amount over several weeks.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): People with IBD, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, should exercise caution. While resistant starch can have prebiotic effects that may benefit gut health, it could also potentially trigger inflammation in some cases. Consultation with a gastroenterologist is critical before incorporating resistant starch into the diet.

- Diabetes: Resistant starch can help improve blood sugar control by slowing the absorption of glucose. However, individuals with diabetes should monitor their blood sugar levels closely, especially when first introducing resistant starch. The glycemic response can vary, and adjustments to medication might be necessary under medical supervision.

- Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity: While many sources of resistant starch are naturally gluten-free (e.g., green bananas, cooked and cooled rice), it’s crucial to verify the processing methods, especially for supplements, to ensure they are free from cross-contamination. Always check product labels for gluten-free certifications.

- Fructose Malabsorption: Some resistant starch sources, particularly those derived from certain types of corn, may contain traces of fructose. Individuals with fructose malabsorption should monitor their tolerance levels carefully, as this could potentially trigger digestive symptoms.

Importance of Consulting with a Healthcare Professional

Before making significant dietary changes, especially when dealing with health conditions or taking medications, consulting with a healthcare professional is essential.

- Personalized Advice: A doctor or registered dietitian can provide personalized advice based on your medical history, current health status, and any medications you are taking. They can help determine the appropriate type and amount of resistant starch for your specific needs.

- Medication Interactions: Resistant starch may affect the absorption of certain medications. A healthcare provider can assess potential interactions and adjust medication dosages if necessary. For example, resistant starch could potentially alter the effectiveness of diabetes medications or other drugs that affect blood sugar.

- Monitoring and Adjustments: Regular check-ups and monitoring are vital, especially when starting a new dietary regimen. Your healthcare provider can track your progress, monitor for any adverse effects, and make adjustments to your diet or medication as needed.

- Addressing Concerns: If you experience any unusual symptoms, such as persistent bloating, abdominal pain, or changes in bowel habits, it’s important to consult your doctor promptly.

Quality and Sourcing of Resistant Starch Supplements

The quality and sourcing of resistant starch supplements can significantly impact their effectiveness and safety.

- Ingredient Purity: Look for supplements that are free from additives, fillers, and artificial ingredients. Read the label carefully to understand the ingredients and ensure they align with your dietary needs.

- Third-Party Testing: Choose supplements that have been tested by third-party organizations for purity and potency. This ensures that the product contains the stated amount of resistant starch and is free from contaminants.

- Source of Resistant Starch: The source of resistant starch can influence its properties. For example, resistant starch type 2 (RS2) from green bananas and RS3 from retrograded starch have different characteristics. Research the source of the resistant starch in the supplement to understand its potential benefits and effects.

- Manufacturing Practices: Choose supplements manufactured in facilities that adhere to good manufacturing practices (GMP). This ensures the products are made to a high standard of quality and safety.

- Reputable Brands: Purchase supplements from reputable brands with a proven track record of quality and customer satisfaction. Reading reviews from other users can provide valuable insights into the product’s effectiveness and tolerability.

Illustrative Examples and Visual Aids

Visual aids significantly enhance understanding and retention of complex information. They transform abstract concepts into easily digestible formats, making the benefits and processes related to resistant starch more accessible. The following sections detail illustrative examples, designed to clarify key aspects of resistant starch and its impact.

Infographic: Benefits of Resistant Starch on Gut Health

An infographic effectively communicates the complex relationship between resistant starch and gut health. This visual tool employs a clear, step-by-step approach to illustrate the positive effects of resistant starch.The infographic’s design begins with a central illustration: a stylized human gut, segmented to highlight the large intestine (colon). The colon is depicted with a vibrant color scheme, showcasing a healthy, balanced gut microbiome.

- Visual Elements:

- Starting Point: The infographic opens with a visual representation of resistant starch, perhaps a stylized image of a whole grain or a cooked potato that has been cooled. A small arrow points from this food source to the digestive system.

- Journey Through the Digestive System: The resistant starch’s path is shown traveling through the stomach and small intestine, where it remains undigested. This portion of the illustration is less active, emphasizing the lack of enzymatic breakdown in these areas.

- Arrival in the Colon: The graphic then focuses on the colon, where the resistant starch encounters the gut microbiome. Here, a burst of activity is depicted with colorful icons representing different types of beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli).

- Fermentation Process: The fermentation process is visually represented with small bubbles or animated icons, symbolizing the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Arrows point from the bacteria to the bubbles, showing the conversion of resistant starch to SCFAs.

- SCFAs and Their Effects: The SCFAs (e.g., butyrate, propionate, acetate) are visually depicted as entering the colon lining. The lining is shown becoming stronger and healthier, with cells tightly connected. This portion could feature icons showing reduced inflammation and improved gut barrier function.

- Benefits Illustrated: Arrows emanate from the healthy colon lining, pointing to key benefits such as improved digestion, enhanced immune function (represented by a stylized immune cell), reduced inflammation (a flame being extinguished), and improved blood sugar control (a glucose molecule with a positive change).

- Textual Elements: The infographic uses concise text to explain each stage. Short, impactful phrases accompany the visuals.

- The initial section explains that resistant starch “passes undigested” through the upper digestive tract.

- The section on the colon highlights the “fermentation by beneficial bacteria” process.

- The production of SCFAs is described as “fuel for colon cells.”

- Benefits are summarized with phrases like “reduced inflammation,” “improved gut barrier,” and “better blood sugar control.”

- Color Palette: A vibrant color scheme is used to maintain visual appeal, with blues and greens representing health and vitality, and warm colors (reds, oranges) used sparingly to indicate potential inflammation or areas of improvement.

Chart: Resistant Starch Content in Different Food Groups

A chart comparing the resistant starch content across various food groups provides a quick and easy reference for dietary planning. The chart is formatted as a table, offering clear comparisons.

- Table Structure: The table is organized with two main columns: “Food Group” and “Resistant Starch Content (per 100g serving)”. The “Food Group” column lists the categories, such as legumes, grains, starchy vegetables, and fruits. The “Resistant Starch Content” column provides numerical values.

- Food Groups Listed:

- Legumes: Examples include lentils, chickpeas, and black beans. The chart specifies the resistant starch content for each. For example, “Lentils: 2.5g,” “Chickpeas: 2.0g,” “Black Beans: 3.0g.”

- Grains: This category includes foods like cooked and cooled rice, oats, and barley. The chart notes the resistant starch content. For example, “Cooked and Cooled Rice: 3.5g,” “Oats (cooked and cooled): 1.5g,” “Barley: 2.0g.”

- Starchy Vegetables: Examples include potatoes (cooked and cooled), green bananas, and sweet potatoes. The chart provides specific values. For example, “Potatoes (cooked and cooled): 4.0g,” “Green Bananas: 5.0g,” “Sweet Potatoes: 1.0g.”

- Fruits: This section includes foods like unripe bananas and other fruits with varying levels. For example, “Unripe Bananas: 4.5g.”

- Data Presentation: The “Resistant Starch Content” column uses clear numerical values, allowing for easy comparison. Values are presented in grams (g) per 100-gram serving.

- Additional Notes: The chart includes a footnote explaining that the resistant starch content can vary based on factors like food preparation (e.g., cooking and cooling) and the specific variety of the food. It might also include a note about the importance of considering the overall dietary context.

Diagram: Resistant Starch Fermentation in the Colon

A diagram detailing the process of resistant starch fermentation in the colon provides a visual representation of the complex biological interactions. The diagram focuses on the key steps involved.

- Central Focus: The diagram’s central element is a cross-section of the colon, showcasing its inner lining (mucosa) and the lumen (the space inside the colon).

- Key Components:

- Resistant Starch Entry: The diagram begins with a visual representation of resistant starch entering the colon. This could be depicted as a chain of glucose molecules, representing the starch.

- Gut Microbiota: A variety of bacteria are illustrated within the colon lumen. These are represented by different shapes and colors to indicate the diversity of the gut microbiome. Key bacterial species, such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, are highlighted.

- Enzymatic Action: Arrows and visual cues show the bacteria interacting with the resistant starch. These arrows represent enzymes secreted by the bacteria that break down the resistant starch molecules.

- SCFAs Production: The breakdown of resistant starch is shown to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). The diagram uses visual representations of these SCFAs (e.g., butyrate, acetate, propionate) with different shapes and colors.

- Colon Lining Interaction: The SCFAs are depicted moving towards and interacting with the colon lining. For example, butyrate is shown fueling the cells that line the colon.

- Benefits Illustrated: The diagram includes icons or illustrations representing the benefits of SCFAs, such as:

- Improved Gut Barrier: Cells of the colon lining are depicted becoming stronger and more tightly connected, preventing “leaky gut.”

- Reduced Inflammation: Icons show reduced inflammation in the colon lining.

- Enhanced Immune Function: Stylized immune cells are depicted interacting with the colon lining, representing improved immune responses.

- Visual Style: The diagram utilizes a clean, scientific style. Color-coding is used to differentiate between different components, and arrows indicate the direction of the processes.

- Annotations: The diagram is annotated with labels to identify the key components and processes. These labels are concise and use scientific terminology (e.g., “resistant starch,” “bacterial fermentation,” “SCFAs,” “butyrate”).

Epilogue

In conclusion, the resistant starch foods list pdf offers a powerful toolkit for optimizing your health. By understanding the science, embracing the food sources, and integrating resistant starch strategically into your diet, you can unlock a wealth of benefits for your gut, your blood sugar, and your overall vitality. Embrace the power of resistant starch and take control of your health journey today.

This guide is not just a list; it’s a pathway to a healthier, more vibrant you.