Food chain sea turtle. The words themselves whisper of a world teeming with life, a ballet of survival played out beneath the waves. Imagine these ancient mariners, gracefully gliding through the sapphire depths, each movement a thread woven into the intricate tapestry of the marine ecosystem. They are not just solitary creatures; they are vital links, playing roles as diverse as they are crucial.

From the sun-drenched shallows to the unexplored abysses, the sea turtle’s journey is a captivating tale of adaptation, resilience, and the delicate balance of nature.

These magnificent reptiles, with their varied diets and unique feeding strategies, shape the very fabric of their underwater homes. Their interactions with other marine species, both symbiotic and competitive, create a dynamic environment where every creature has a part to play. But this intricate web is facing unprecedented threats. Plastic pollution, habitat destruction, and the impact of human activities cast a long shadow, threatening the very existence of these ancient mariners and the delicate food chains they anchor.

Let’s delve deeper into the lives of these fascinating creatures, exploring their place in the food web and the urgent need for their conservation.

Sea Turtle’s Place in the Marine Food Web

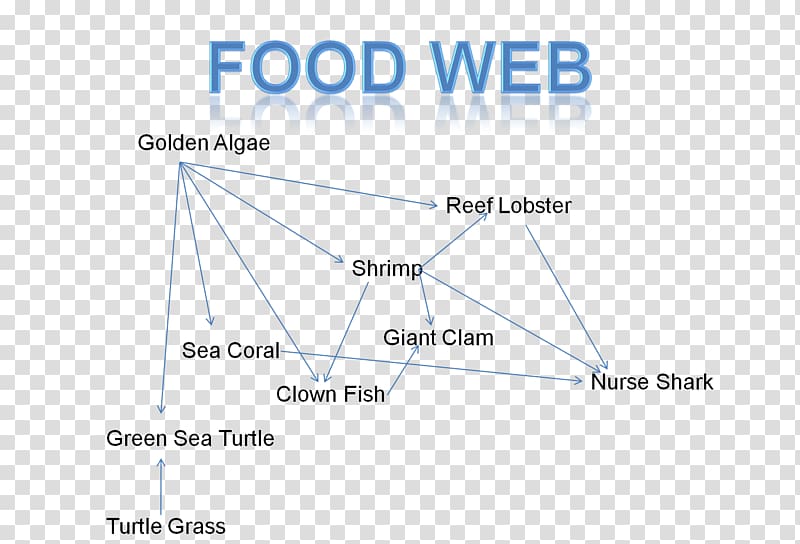

The ocean’s depths harbor a complex network of life, a delicate dance of predator and prey where energy flows through intricate food webs. Sea turtles, ancient mariners of the deep, occupy a pivotal role in these ecosystems, their presence shaping the very fabric of marine life. Their position varies depending on the species and the environment, yet their impact is undeniable.

Finish your research with information from mice proof food storage.

Sea Turtle’s Role as Consumers

Sea turtles are primarily consumers, obtaining energy by feeding on a variety of organisms. Their diets are as diverse as the habitats they inhabit. Understanding their feeding habits provides insight into their ecological significance.

- Herbivores: Some sea turtle species, like the green sea turtle ( Chelonia mydas), are primarily herbivores in their adult stage. They graze on seagrass and algae, playing a crucial role in maintaining the health of seagrass beds.

Seagrass beds, akin to underwater meadows, provide habitat and shelter for numerous other marine species. By keeping seagrass in check, green sea turtles prevent overgrowth and ensure the health of the entire ecosystem.

- Carnivores/Omnivores: Other species, such as the loggerhead sea turtle ( Caretta caretta) and the hawksbill sea turtle ( Eretmochelys imbricata), are omnivores or carnivores. Their diets consist of a variety of prey, including jellyfish, sponges, crabs, and other invertebrates.

Loggerheads, with their powerful jaws, are well-suited to crushing shellfish. Hawksbills, on the other hand, have a more specialized beak that allows them to reach into crevices to feed on sponges.

The hawksbill’s diet contributes to coral reef health by controlling sponge populations.

- Dietary Specialization: Certain sea turtle species exhibit dietary specializations. For example, the leatherback sea turtle ( Dermochelys coriacea) almost exclusively consumes jellyfish.

Leatherbacks possess backward-pointing spines in their mouths and throats, which help them to trap and swallow jellyfish, preventing them from escaping. This specialization makes them effective controllers of jellyfish populations.

Sea Turtle’s Role as Predators and Prey

Sea turtles are not only consumers; they are also both predators and prey within the marine food web. Their position in this delicate balance shifts depending on their life stage and the specific ecosystem.

- Predators: Juvenile sea turtles and even adult turtles can be preyed upon by various predators. Sharks, such as tiger sharks, are known predators of sea turtles.

In some regions, killer whales (orcas) also prey on sea turtles. The size and strength of these predators make sea turtles vulnerable, particularly when they are young or weakened.

- Prey: While adult sea turtles have fewer natural predators due to their size and hard shells, they still face threats.

Sea turtle eggs and hatchlings are especially vulnerable to predation by various animals, including crabs, birds, raccoons, and foxes, depending on the nesting location.

- Examples in Different Ecosystems: The food web dynamics vary depending on the ecosystem. In coral reefs, hawksbills help control sponge populations.

In seagrass beds, green sea turtles graze on seagrass, influencing the health of the ecosystem. In open ocean environments, leatherbacks consume jellyfish, which may have cascading effects on other species.

Sea Turtle Diet and Feeding Habits: Food Chain Sea Turtle

The ocean’s silent ballet, a world of shifting currents and hidden dangers, holds a truth about sea turtles: their lives are dictated by their appetites. From the moment they hatch and scramble toward the sea, to their twilight years, feeding is a constant imperative. The diverse feeding strategies employed by these ancient mariners are as varied as the ocean’s menu, a testament to their adaptability and the subtle, often unseen, connections within the marine ecosystem.

Diverse Feeding Strategies

Sea turtles, ancient navigators of the deep, are not picky eaters. They are opportunistic feeders, employing a range of strategies to acquire sustenance, their diets shaped by their species, age, and the resources available in their habitat.They might be grazing on the lush seagrass meadows, or consuming the stinging embrace of jellyfish, or even crunching through the shells of crustaceans.The Green Sea Turtle, a true herbivore in adulthood, exemplifies the art of grazing.

Their finely serrated jaws are perfectly adapted for cropping seagrass and algae, a crucial task that helps maintain the health of these underwater ecosystems.Hawksbill turtles, with their sharp, beak-like mouths, are the skilled hunters of the coral reefs. They navigate the intricate labyrinths of the coral, seeking out sponges, their primary food source.Leatherback turtles, the largest of all sea turtles, have a diet focused on jellyfish.

Their spiky papillae, which line their mouths and throats, act like a sieve, ensuring the slippery, gelatinous prey doesn’t escape.Loggerhead turtles, with powerful jaws, crush the shells of crabs and mollusks, revealing the hidden treasures within.

Dietary Differences Between Juvenile and Adult Sea Turtles

The dietary preferences of sea turtles undergo a significant transformation as they mature. This shift reflects both physiological changes and a strategic adaptation to different ecological niches. Juvenile turtles, facing the perils of the open ocean, often adopt a more omnivorous diet, while adults tend to specialize.

- Juvenile Diet:

- Omnivorous: Young sea turtles often consume a mix of food items, including small invertebrates, jellyfish, and algae. This dietary flexibility helps them survive in the open ocean where food resources can be unpredictable.

- Adaptation to Open Ocean: Their smaller size and need for rapid growth necessitate a diet that provides a broad range of nutrients.

- Adult Diet:

- Specialized: Adult sea turtles typically adopt a more specialized diet based on their species. For example, green sea turtles become primarily herbivorous, while leatherbacks specialize in jellyfish.

- Habitat-Specific: As they mature, sea turtles often migrate to feeding grounds that offer the specific food sources they require.

Common Food Items and Adaptations

The remarkable diversity of sea turtle diets is matched by the unique adaptations they have developed to exploit their food sources.

| Sea Turtle Species | Common Food Items | Adaptations for Consumption | Illustration (Description) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) | Seagrass, algae | Finely serrated jaws for cropping vegetation. | A Green Sea Turtle is depicted grazing on lush green seagrass, its mouth perfectly adapted for cropping the blades. The turtle’s streamlined body and flippers allow it to move efficiently through the water while feeding. The scene highlights the crucial role these turtles play in maintaining the health of seagrass ecosystems. |

| Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) | Sponges, tunicates | Sharp, beak-like mouth for scraping and tearing; strong jaws for crushing. | A Hawksbill Sea Turtle is shown meticulously navigating the complex architecture of a coral reef. The turtle’s head is close up, showcasing the beak-like mouth that it uses to extract sponges and other organisms from the crevices of the coral. The intricate patterns of the coral and the surrounding marine life emphasize the Hawksbill’s role within the reef ecosystem. |

| Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) | Jellyfish, salps | Spiky papillae lining the mouth and throat to trap slippery prey. | A Leatherback Sea Turtle is shown with its mouth open, revealing the numerous, backward-pointing spines that line its mouth and throat. The image suggests the interior of the mouth, highlighting the adaptations that allow it to efficiently consume jellyfish and other gelatinous prey. The size of the turtle is implied through the detail of its mouth structure. |

| Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta) | Crabs, mollusks | Powerful jaws for crushing hard shells. | A Loggerhead Sea Turtle is depicted with its strong jaws clamping down on a crab. The image focuses on the turtle’s head, highlighting the robust jaw structure and the strength it uses to break the crab’s shell. The background shows the ocean floor and surrounding marine life, showcasing the turtle’s natural habitat. |

Predators of Sea Turtles

The ocean’s depths hold secrets, and within them, the life of a sea turtle is a constant dance with danger. From the moment they hatch, these ancient mariners face a gauntlet of predators, each seeking a meal. The predator-prey relationship is a delicate balance, a silent struggle that shapes the survival of these magnificent creatures and the health of the marine ecosystem.

Let’s delve into the shadows and uncover the hunters that stalk sea turtles at every stage of their lives.

Natural Predators at Different Life Stages

The vulnerability of a sea turtle varies dramatically depending on its size and life stage. Young turtles are especially defenseless, facing a barrage of threats, while adults, protected by their shells, have fewer natural predators.

Here’s a glimpse into the predators that sea turtles encounter throughout their journey:

- Eggs and Hatchlings: The journey begins with a perilous race against time.

Eggs, buried in the sand, are vulnerable to a variety of predators. Hatchlings, emerging from their nests, are easy targets.

The most common predators at this stage include:

- Crabs: Ghost crabs and other species are known to dig up and consume sea turtle eggs.

- Birds: Gulls, frigatebirds, and other seabirds swoop down to snatch hatchlings as they emerge from their nests and make their dash to the ocean. Imagine a wide, sandy beach under a scorching sun. A flock of gulls circles above, their sharp eyes scanning the sand. Below, a tiny sea turtle, barely bigger than a human hand, struggles towards the waves, unaware of the aerial predators above.

This is the harsh reality for newly hatched sea turtles.

- Mammals: Foxes, raccoons, and other terrestrial mammals may dig up nests to consume eggs or prey on hatchlings.

- Juveniles: Once in the water, young turtles face new threats.

As they grow, juvenile sea turtles are still vulnerable, though their size offers some protection.Common predators include:

- Large Fish: Sharks, groupers, and other large predatory fish will readily consume juvenile sea turtles.

- Seabirds: Larger seabirds, like the magnificent frigatebird, continue to prey on juvenile turtles, especially those near the surface. Picture a clear, tropical ocean. A juvenile sea turtle, maybe the size of a dinner plate, swims near the surface, feeding on seaweed. Suddenly, a frigatebird, with its characteristic forked tail, dives from above, attempting to snatch the turtle from the water.

The turtle dives, but the bird remains a constant threat.

- Adults: Adult sea turtles, protected by their shells, have fewer predators.

However, even adults are not entirely safe.The primary predator of adult sea turtles is:

- Sharks: Large sharks, such as tiger sharks, are known to prey on adult sea turtles. They may target vulnerable turtles or those that are injured or ill. Consider the image of a vast, blue ocean. A massive tiger shark, its stripes barely visible in the depths, circles a sea turtle, its powerful jaws a constant threat. The turtle, though protected by its shell, faces a formidable adversary.

Impact of Predator-Prey Relationships on Sea Turtle Populations

The constant pressure from predators has a profound impact on sea turtle populations. Survival rates vary greatly depending on the life stage, and this, in turn, influences the overall health and stability of the populations.

Here’s how predator-prey dynamics affect sea turtle populations:

- High Mortality in Early Life Stages: The majority of sea turtle mortality occurs during the egg and hatchling stages.

Many eggs are consumed before they hatch, and a significant percentage of hatchlings are eaten by predators before reaching the ocean.

Example: In some areas, less than 1% of hatchlings survive to adulthood, highlighting the extreme vulnerability of young sea turtles.

- Predator-Driven Selection: Predation can influence the evolution of sea turtle traits.

For example, hatchlings that are faster or better camouflaged have a higher chance of survival, leading to natural selection favoring these traits.

Example: The speed at which a hatchling can reach the water, or the coloration of its shell, can determine its fate in the face of a hungry predator.

- Population Regulation: Predator-prey relationships help regulate sea turtle populations.

Predators can limit population growth, preventing overcrowding and resource depletion.

Example: If sea turtle populations increase significantly, predator populations may also increase, leading to a natural balancing act.

Human Activities and Altered Predator-Prey Dynamics

Human activities have significantly altered the predator-prey dynamics in the sea turtle food chain, often to the detriment of sea turtle populations. Pollution, habitat destruction, and overfishing have all played a role.

Here are some ways human activities have changed the balance:

- Habitat Destruction: Coastal development and other forms of habitat destruction have reduced nesting sites and feeding grounds for sea turtles.

This forces turtles into more dangerous areas, increasing their exposure to predators.

Example: The loss of nesting beaches due to beachfront construction reduces the available space for turtles to lay their eggs, making them more vulnerable to predators.

- Pollution: Pollution, including plastic debris, can indirectly affect predator-prey relationships.

Turtles may ingest plastic, weakening them and making them easier prey.

Example: A sea turtle, weakened by ingesting plastic bags, becomes a more vulnerable target for sharks or other predators.

- Overfishing: Overfishing can disrupt the marine ecosystem, affecting predator populations.

The removal of large predatory fish can sometimes lead to an increase in the populations of smaller predators, such as certain types of crabs, which then prey more heavily on sea turtle eggs and hatchlings.

Example: The decline of shark populations due to overfishing could, in some cases, lead to an increase in the populations of other predators of sea turtles, such as smaller fish or crabs.

- Bycatch: Sea turtles are often caught as bycatch in fishing gear, which can lead to their injury or death.

This reduces the number of breeding adults, impacting population numbers.

Example: Sea turtles caught in fishing nets may be injured, making them easier prey for sharks or other predators.

Threats to the Sea Turtle Food Chain

The sea, a realm of ancient secrets and shifting tides, holds a delicate balance. Within this watery world, the sea turtle, a creature of immense age and grace, plays a vital role. But shadows loom, and the threads that connect life within the ocean are fraying. The very existence of these ancient mariners, and the ecosystems they inhabit, face an onslaught of threats, each one a potential domino in a cascade of ecological collapse.

The fate of the sea turtle is intertwined with the fate of the entire marine food web, and the consequences of their decline ripple outwards, affecting everything from seagrass beds to coral reefs.

Major Threats to Sea Turtle Populations and the Food Chain Consequences

The decline of sea turtle populations is not merely a tragedy for these individual creatures; it represents a significant disruption to the intricate web of life within the oceans. These threats are multifaceted and often interconnected, exacerbating their impact on the food chain.

- Bycatch in Fishing Gear: This is a leading cause of sea turtle mortality. Turtles are frequently caught in nets and on longlines, often drowning or suffering severe injuries. The removal of turtles disrupts the food chain in several ways. For instance, a reduction in turtle populations can lead to overgrazing of seagrass beds, as turtles are primary consumers of seagrass. This can lead to habitat degradation, impacting other species that rely on these seagrass meadows for food and shelter, such as juvenile fish and invertebrates.

This in turn affects the availability of food for larger predators, creating a cascading effect.

- Habitat Destruction and Degradation: Coastal development, including the construction of hotels, resorts, and marinas, destroys nesting beaches and feeding grounds. Pollution, including chemical runoff and sewage, further degrades these habitats. The loss of nesting beaches directly impacts the reproductive success of sea turtles, leading to fewer hatchlings and a decline in population numbers. Degradation of feeding grounds, such as coral reefs and seagrass beds, reduces the food available to turtles, impacting their growth, health, and reproductive capabilities.

The loss of habitat also affects the species that depend on the same resources as sea turtles. For example, a decline in coral reefs due to habitat destruction will affect the fish species that feed on them, impacting the whole marine food web.

- Climate Change: Rising sea temperatures and altered weather patterns pose a significant threat. Increased sea levels erode nesting beaches, while more frequent and intense storms can destroy nests and wash away hatchlings. Changes in ocean currents and water temperatures also affect the distribution of prey species, making it more difficult for turtles to find food. Furthermore, the sex of sea turtle hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the nest; warmer temperatures lead to more females, potentially disrupting the population sex ratio.

This can lead to a decrease in reproductive success and a long-term decline in turtle populations.

- Pollution: Pollution, including chemical runoff and plastic debris, poses a grave threat. Sea turtles ingest plastic, mistaking it for food, leading to starvation, internal injuries, and blockages in their digestive systems. Chemical pollutants can bioaccumulate in turtles, harming their health and reproductive capabilities. Plastic pollution, in particular, has devastating consequences.

Impact of Plastic Pollution on Sea Turtles and the Broader Marine Ecosystem

Plastic pollution, a pervasive and growing threat, is a significant contributor to sea turtle mortality and poses widespread ecological harm. The very nature of plastic, its durability and slow degradation, ensures its longevity in the marine environment, making it a persistent danger.

- Ingestion of Plastic: Sea turtles often mistake plastic bags and other debris for jellyfish, their primary food source. Ingesting plastic can lead to a variety of problems, including:

- Starvation: Plastic fills the stomach, creating a false sense of fullness, preventing turtles from consuming actual food.

- Internal Injuries: Sharp plastic fragments can puncture internal organs, causing infections and internal bleeding.

- Blockages: Plastic can block the digestive tract, preventing the absorption of nutrients and leading to starvation.

- Entanglement: Sea turtles can become entangled in plastic debris such as fishing gear, plastic six-pack rings, and discarded plastic ropes. Entanglement can lead to:

- Drowning: Turtles may become trapped underwater and drown.

- Impaired Movement: Entanglement can restrict movement, making it difficult for turtles to find food or escape predators.

- Wounds and Infections: Entanglement can cause severe injuries, leading to infections and death.

- Bioaccumulation of Toxins: Plastic absorbs and concentrates toxins from the surrounding environment. When sea turtles ingest plastic, these toxins can accumulate in their tissues, leading to:

- Reproductive Problems: Toxins can interfere with reproduction, reducing the number of eggs laid or hatching success.

- Weakened Immune Systems: Exposure to toxins can weaken the immune system, making turtles more susceptible to diseases.

- Impact on the Broader Ecosystem: The impact of plastic pollution extends beyond sea turtles, affecting the entire marine ecosystem. Plastic debris can:

- Smother Habitats: Plastic can accumulate on the seafloor, smothering coral reefs and seagrass beds, which are crucial habitats for many marine species.

- Transport Invasive Species: Plastic can act as a raft, transporting invasive species to new environments, disrupting native ecosystems.

- Introduce Toxins: Plastic can release harmful chemicals into the water, affecting the health of marine organisms throughout the food web.

Methods to Mitigate the Threats Sea Turtles Face

Addressing the threats facing sea turtles requires a multifaceted approach involving conservation efforts, policy changes, and public awareness. The following methods are crucial for protecting sea turtles and their habitats.

- Reduce Bycatch: Implement and enforce regulations requiring the use of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in fishing nets. These devices allow turtles to escape from nets, significantly reducing bycatch mortality. Promote the use of fishing gear that minimizes bycatch, such as circle hooks.

- Protect and Restore Habitats: Establish and protect marine protected areas (MPAs) that encompass important nesting beaches and feeding grounds. Implement coastal management plans that restrict development in sensitive areas and promote sustainable practices. Restore degraded habitats, such as coral reefs and seagrass beds.

- Combat Climate Change: Reduce greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate climate change. Support research on the impacts of climate change on sea turtles and their habitats. Implement measures to protect nesting beaches from erosion, such as beach nourishment and dune restoration.

- Reduce Plastic Pollution: Implement and enforce regulations to reduce plastic production and waste. Promote the use of reusable alternatives to single-use plastics. Improve waste management and recycling infrastructure. Participate in beach cleanups and support organizations that remove plastic from the ocean.

- Enforce Existing Regulations: Stricter enforcement of existing laws, such as those prohibiting the poaching of turtles and the illegal trade of turtle products, is essential.

- Raise Public Awareness: Educate the public about the threats facing sea turtles and the importance of conservation. Support conservation organizations and initiatives. Encourage responsible tourism practices.

- International Cooperation: Collaborate with other countries to protect sea turtles and their habitats, as turtles often migrate across international borders. Share best practices and coordinate conservation efforts.

- Conduct Research and Monitoring: Conduct research on sea turtle populations, their habitats, and the threats they face. Monitor sea turtle populations to track their progress and adapt conservation strategies as needed.

The Impact of Sea Turtle Decline

The emerald depths hold secrets, and among them, the fate of the sea turtle is intertwined with the health of the entire ocean. Their decline casts a long shadow, a ripple effect that touches countless other creatures and subtly shifts the delicate balance of the marine world. It’s a story of interconnectedness, where the absence of one player can unravel the intricate web of life.

Ecological Consequences of Declining Sea Turtle Populations

The loss of sea turtles triggers a cascade of effects, reshaping habitats and impacting the abundance of other species. Their roles as grazers, predators, and nutrient transporters are crucial for ecosystem health. As their numbers dwindle, the consequences become increasingly apparent.

- Changes in Seagrass Beds: Sea turtles, particularly green sea turtles, graze on seagrass, keeping it healthy and preventing overgrowth. Without them, seagrass beds can become overgrown, reducing biodiversity and impacting the habitats of numerous other species. The overgrown seagrass can also lead to reduced oxygen levels in the water, harming marine life.

- Altered Coral Reef Dynamics: Hawksbill sea turtles, with their specialized beaks, feed on sponges that can overgrow coral reefs. A decrease in hawksbill populations allows sponges to proliferate, potentially smothering and damaging coral reefs. This loss of coral reefs, in turn, affects the countless species that depend on them for shelter and food.

- Reduced Nutrient Cycling: Sea turtles play a role in nutrient cycling, transporting nutrients from feeding grounds to nesting beaches and back into the marine environment. Their waste and decomposing bodies contribute to the nutrient pool, benefiting various marine organisms. A decline in their populations can disrupt this essential nutrient flow.

- Increased Jellyfish Blooms: Leatherback sea turtles have a diet primarily of jellyfish. Their decline has been linked to an increase in jellyfish populations in some areas. These blooms can disrupt the food web, competing with other species for resources and potentially harming humans.

How the Loss of Sea Turtles Can Affect Other Species in the Marine Food Web

The removal of sea turtles from the food web creates a void, a gap that other species struggle to fill. This disruption can lead to population imbalances and shifts in species distributions. The decline impacts both predators and prey, altering the intricate relationships within the marine ecosystem.

- Impact on Predators: Predators of sea turtles, such as sharks, may experience a decrease in their food supply. This can lead to reduced reproductive success and changes in their population dynamics.

- Impact on Prey Species: The absence of sea turtles can lead to changes in the abundance of their prey. For example, an increase in sponge populations (due to the decline of hawksbill turtles) can negatively impact the species that feed on sponges.

- Competition for Resources: The altered balance can intensify competition for resources among the remaining species. This can lead to shifts in the structure of the marine community.

- Changes in Species Distributions: Some species may migrate or alter their behavior in response to the changes in the food web, further disrupting the ecosystem.

The delicate balance of the marine ecosystem hinges on the presence of sea turtles. Their decline, a consequence of human activities and environmental pressures, is not merely the loss of a single species. It is a disruption of a complex network, a cascade of consequences that ripple through the ocean, affecting countless other creatures and ultimately, the health of the planet.

Sea Turtle Conservation Efforts and the Food Chain

Whispers of the ocean’s plight echo through the coral reefs, a chilling tale of imbalance and fragility. Protecting the ancient mariners, the sea turtles, is not merely about saving a single species; it is about safeguarding the intricate tapestry of life woven within the marine food web. The fate of the sea turtle is inextricably linked to the well-being of countless other creatures, and the conservation efforts we undertake ripple outwards, impacting the entire ecosystem.

Examples of Conservation Initiatives, Food chain sea turtle

Conservation initiatives are as diverse as the turtles themselves, spanning from protecting nesting sites to combating plastic pollution. These efforts are crucial for bolstering sea turtle populations and, consequently, the health of their food chain.

- Protected Nesting Sites: Establishing protected areas along coastlines where sea turtles nest is a fundamental conservation strategy. These sanctuaries minimize human interference, such as beach development and artificial lighting, which can disorient hatchlings. This directly increases the survival rate of hatchlings, allowing more turtles to enter the food web and contributing to the stability of populations.

- Reducing Bycatch: Many sea turtles are accidentally caught in fishing gear, known as bycatch. Implementing turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in fishing nets allows turtles to escape, significantly reducing mortality rates. This safeguards adult turtles, which are crucial for maintaining population numbers and contributing to the food chain through their feeding habits.

- Combating Plastic Pollution: Sea turtles often mistake plastic bags for jellyfish, a primary food source. Cleaning up plastic debris from the ocean and reducing plastic production helps to mitigate this threat. This protects turtles from ingestion and entanglement, allowing them to thrive and fulfill their role in the ecosystem.

- Habitat Restoration: Restoring degraded habitats, such as seagrass beds and coral reefs, is vital. These habitats provide food and shelter for many species, including the sea turtles’ prey. A healthy habitat supports a more robust food chain, benefiting the turtles indirectly.

Importance of Habitat Preservation

The preservation of sea turtle habitats is paramount. A healthy habitat provides the resources needed for all life stages of the sea turtle, and supports the complex web of organisms that they interact with. Without these safe havens, the food chain unravels.

“Habitat loss is one of the most significant threats to sea turtle survival, directly impacting their access to food, nesting sites, and shelter.”

The protection of critical habitats ensures the availability of food sources, such as seagrass, jellyfish, and crustaceans, and reduces the risk of predation. This leads to increased sea turtle populations, and therefore a more robust food chain. For instance, consider the Great Barrier Reef. Its health directly impacts the green sea turtle population, which in turn affects the seagrass beds, a crucial food source for dugongs.

The intricate connections between species within this environment highlight the importance of holistic habitat preservation.

Conservation Efforts and Food Chain Benefits

The following table summarizes how different conservation efforts contribute to a healthier marine food chain.

| Conservation Effort | Sea Turtle Benefit | Impact on Prey Species | Ecosystem-Wide Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Nesting Sites | Increased hatchling survival, leading to a larger adult population. | Indirectly benefits prey species by maintaining a balanced predator-prey relationship. | Contributes to overall biodiversity and ecosystem stability by supporting the base of the food chain. |

| Reducing Bycatch | Increased survival of adult sea turtles, allowing them to reproduce and contribute to the food web. | Lessens pressure on prey species by reducing adult turtle mortality. | Reduces the impact of human activities on the marine environment. |

| Combating Plastic Pollution | Reduces ingestion and entanglement, improving overall health and survival rates. | Indirectly benefits prey species by reducing the impact of plastic on the food web. | Creates a cleaner and healthier environment for all marine life. |

| Habitat Restoration | Provides access to food sources and shelter, supporting growth and reproduction. | Supports the health of prey species and increases their abundance. | Enhances overall ecosystem health and biodiversity, promoting a balanced food web. |

Sea Turtle Interactions with Other Marine Species

The ocean’s depths hold a silent ballet of life, a dance of survival where every creature plays a role. Sea turtles, ancient mariners of the deep, are no exception. Their interactions with other marine species paint a vivid picture of cooperation and competition, a constant struggle for existence in a world teeming with life and shrouded in mystery. Let us delve into the intricate relationships that sea turtles forge, uncovering the secrets of their survival.

Symbiotic Relationships

Sea turtles are not solitary wanderers; they often enter into mutually beneficial relationships with other marine organisms. These symbiotic partnerships are crucial for their health and well-being, shaping their interactions with the underwater world.

- Remoras and Sea Turtles: Remoras, also known as suckerfish, attach themselves to sea turtles using a suction cup on their heads. They hitch a ride, gaining transportation and protection from predators. In return, they eat parasites and algae off the turtle’s shell, providing a cleaning service. This is a classic example of commensalism, where one species benefits, and the other is neither harmed nor helped.

Imagine a tiny, streamlined fish, clinging effortlessly to the massive shell of a loggerhead, a mobile home offering both safety and a ready supply of food.

- Cleaning Stations: Sea turtles visit cleaning stations, areas where smaller fish, such as wrasses, gather. These fish meticulously remove parasites and algae from the turtles’ shells and skin. The turtles benefit from parasite removal, and the cleaner fish get a readily available food source. The scene is one of mutual grooming, a silent pact of cleanliness in the bustling coral reef.

Picture a hawksbill turtle, patiently allowing a swarm of tiny fish to work, the vibrant colors of the cleaners a stark contrast to the turtle’s shell.

- Coral Reef Ecosystems: Sea turtles, particularly green sea turtles, graze on seagrass and algae in coral reef ecosystems. This grazing helps to maintain the health of these ecosystems by preventing overgrowth and promoting biodiversity. Their grazing habits prevent the seagrass from becoming too dense, which can lead to oxygen depletion. In turn, the healthy ecosystems provide food and shelter for a myriad of other marine species, benefiting the entire food web.

Consider the vast seagrass meadows, kept in balance by the constant grazing of the green turtles, ensuring a healthy habitat for countless other creatures.

Competitive Interactions

The ocean is a realm of limited resources, and sea turtles are not immune to the competition for food and habitat. They often clash with other species for survival.

- Competition for Food: Sea turtles, depending on their species and life stage, compete with various marine animals for food resources. For example, green sea turtles compete with manatees for seagrass. Loggerhead sea turtles compete with other predators like sharks and large fish for jellyfish and crustaceans. Leatherback sea turtles, with their specialized diet of jellyfish, may face competition from other gelatinous-eating species.

This struggle for sustenance is a constant reality in the marine environment.

- Habitat Overlap: Sea turtles share habitats with other marine creatures, leading to potential competition for space and resources. Coastal areas, nesting beaches, and foraging grounds can become crowded, leading to conflict. This competition is particularly evident on nesting beaches, where sea turtles compete with other species like shorebirds and crabs for nesting sites. The competition intensifies when resources are scarce, and the need to survive becomes more pressing.

- Predation and Avoidance: While sea turtles are apex predators in some ecosystems, they are also preyed upon by other marine species, particularly during their early life stages. Sharks, killer whales, and large fish are known predators of sea turtles. This threat forces sea turtles to develop strategies to avoid predation, such as camouflage, rapid swimming, and seeking shelter in reefs or seagrass beds.

This constant pressure from predators shapes their behavior and survival strategies.

Examples of Sea Turtle Interactions

The ocean’s interactions are dynamic and varied. Here are some specific examples.

- Green Sea Turtles and Seagrass: Green sea turtles graze on seagrass, keeping it healthy and preventing overgrowth.

- Loggerhead Sea Turtles and Jellyfish: Loggerhead sea turtles feed on jellyfish, competing with other predators like certain fish.

- Hawksbill Sea Turtles and Coral Reefs: Hawksbill sea turtles consume sponges in coral reefs, contributing to the health of the reef ecosystem.

- Sea Turtles and Remoras: Remoras attach to sea turtles, gaining transportation and feeding on parasites.

- Sea Turtles and Sharks: Sharks prey on sea turtles, particularly young ones, influencing their behavior and survival.

- Sea Turtles and Cleaner Fish: Cleaner fish remove parasites from sea turtles, providing a cleaning service.

- Sea Turtles and Humans: Humans pose a significant threat to sea turtles through fishing, habitat destruction, and pollution.

The Role of Sea Turtles in Nutrient Cycling

The ocean’s depths hold secrets, whispered on the currents. Among them, the silent ballet of life and death, of feast and famine, is governed by the unseen hand of nutrient cycling. Sea turtles, ancient mariners of the deep, play a crucial role in this intricate dance, their very existence shaping the health and vitality of the marine world. They are not merely consumers; they are architects of the ecosystem, their presence weaving a tapestry of life.

Sea Turtle Contribution to Nutrient Cycling

Sea turtles, through their feeding and waste production, act as crucial players in the nutrient cycle. Their activities contribute significantly to the distribution and availability of essential elements within marine ecosystems.The contribution to nutrient cycling can be detailed as follows:

- Fecal Matter as Fertilizer: Sea turtle excrement, rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and other essential nutrients, acts as a natural fertilizer. This waste, deposited in various locations, from nesting beaches to feeding grounds, fuels the growth of primary producers like algae and seagrass. This, in turn, supports the entire food web.

- Benthic Nutrient Transfer: By grazing on seagrass and algae, sea turtles release nutrients from the seabed into the water column. This process, known as bioturbation, enhances the availability of nutrients for other organisms. Imagine a vast, underwater garden, where turtles act as gentle cultivators, stirring the soil to bring forth life.

- Nesting Beach Nutrient Input: When female sea turtles come ashore to nest, they transport nutrients from the ocean to the terrestrial environment. Their eggs and decomposing bodies provide a concentrated source of nutrients to the beach ecosystem, supporting the growth of vegetation and the food web of the dune environment.

Importance of Sea Turtle Waste in Supporting Marine Life

The waste produced by sea turtles is not merely a byproduct of their existence; it’s a vital resource for a multitude of marine organisms. This waste provides a crucial link in the food web, supporting life at various trophic levels.The importance of sea turtle waste can be elaborated as follows:

- Fueling Primary Production: The nitrogen and phosphorus in sea turtle waste stimulate the growth of phytoplankton and seagrass, the foundation of the marine food web. This increased primary production supports a greater abundance of other marine life.

- Supporting Detritivores: Sea turtle waste is consumed by detritivores, such as certain species of worms and crustaceans. These organisms break down the waste, releasing nutrients back into the environment and providing a food source for other species.

- Attracting Scavengers: Decomposing sea turtle carcasses, both on land and in the water, attract scavengers, from crabs and seabirds to sharks. This provides a temporary but significant food source, especially in nutrient-poor environments.

Impact of Sea Turtles on Nutrient Distribution

Sea turtles are active participants in distributing nutrients throughout the marine environment. Their movements and feeding habits contribute to the spatial and temporal distribution of essential elements, impacting the overall health and productivity of the ecosystem.The impact of sea turtles on nutrient distribution can be summarized as follows:

- Seagrass Meadows: By grazing on seagrass, sea turtles stimulate its growth and health. They also help to prevent the overgrowth of seagrass, ensuring that the nutrients are distributed evenly throughout the meadow. The areas where turtles graze on seagrass have a higher concentration of nutrients, which helps in maintaining the ecosystem balance.

- Migration Patterns: The long-distance migrations of sea turtles contribute to the dispersal of nutrients across vast oceanic regions. For example, sea turtles may feed in nutrient-rich areas and then migrate to nesting beaches, transporting nutrients over great distances.

- Coral Reefs: Sea turtles contribute to the health of coral reefs by controlling the populations of algae and other organisms that can overgrow and smother the coral. The presence of sea turtles also helps to cycle nutrients within the reef ecosystem, supporting the growth of corals and other reef inhabitants.

Final Summary

In the end, the food chain sea turtle story is a testament to the interconnectedness of life. From the smallest plankton to the largest whale, every creature plays a part in this grand drama. The fate of the sea turtle is intertwined with the health of the oceans themselves. By understanding their place in the food web, recognizing the threats they face, and supporting conservation efforts, we can help ensure that these graceful giants continue to roam the seas for generations to come.

Let’s work together to protect not only the sea turtle, but the entire underwater world they call home.